Well-known Christian apologist Dr. Frank Turek recently posted a short clip explaining his two main objections to Calvinism:

1. that it makes the world feel like a sham because God commands choices people cannot make, and

2. that it makes God the author of evil. Turek mentioned in the video clip about how his mentor, the late Dr. Norman Geisler, called hardcore Calvinism a “contradiction.”

Here is the post he shared (embedded below):

Where Does Calvinism Go Wrong? #Theology pic.twitter.com/xaFK8Oe9sr

— Frank Turek (@DrFrankTurek) December 24, 2025

A Brief Disclaimer Before We Dig In

I want to say up front that I highly respect both Norman Geisler and Frank Turek. God has used these two apologists in remarkable ways to defend the Christian faith, strengthen believers, and answer real objections. Both have been brilliant and highly gifted. I am grateful for them and their work.

One of my earliest apologetic memories was in the 1980s when Geisler appeared on the John Ankerberg Show defending Christianity against atheist and secular humanist Paul Kurtz. He had such a logical (and biblical) explanation for everything, I wondered why anyone would remain a skeptic when it came to Christ’s claims (I was young, and my soteriology was not as developed as it is nowadays).

At the same time, I believe their objections to Calvinism miss the heart of the Reformed (and biblical) position, and I also believe Dr. Geisler’s “contradiction” charge against John Gerstner is mistaken. In my view, the issue is not that Calvinism collapses into incoherence. The issue is that certain critics assume a definition of freedom, causation, and moral responsibility that the Bible itself does not assume.

Response Via Tod Ashby on X

Tod Ashby, an X (AKA Twitter) user, has been someone I’ve gotten to know to have some very well-rounded and astute theological observations, especially when it comes to Calvinism/Reformed thought, and has offered a thoughtful response to Turek in two X posts.

Now, usually, I hate the type of news articles or blog pieces that make sensationalist topics out of someone “owning” someone else in a social media post. Most of them are very shallow at best, and they almost never do anything to advance civil discourse, especially in Christian circles.

But I do happen to agree very strongly with what Ashby has said in these posts, and I could not have answered these better myself; so I will link to and post Ashby’s comments in their entirety, occasionally breaking to insert my own comments.

I am going to embed both posts, then I will reproduce the full text of each one, broken into sections. I will put Ashby’s words in bold, and I will pause between key points to explain things in plain language.

By the way, be sure to give Tod Ashby a follow if you’re on X/Twitter.

Tod Ashby’s first response (embedded)

Turek’s clip trades on a familiar sleight of hand. He redefines Calvinism as fatalism, smuggles in a libertarian definition of freedom, and then declares victory when the Reformed position fails to meet standards it never accepted. It sounds persuasive until you actually examine… https://t.co/9fRpC23I6i

— Tod Ashby (@TodAshby) December 24, 2025

Tod Ashby’s follow-up response (embedded)

First, Turek slightly misstated the exchange between Gerstner and Geisler. John Gerstner did not argue that “God gives man the desire of his heart” in some crude, mechanical sense, as though desires are injected wholesale. He was defending the Edwardsian point that the will… https://t.co/a3fMx3P0pZ pic.twitter.com/7jtHZqNtQc

— Tod Ashby (@TodAshby) December 26, 2025

Ashby’s first post (full text with my commentary)

Ashby: Turek’s clip trades on a familiar sleight of hand. He redefines Calvinism as fatalism, smuggles in a libertarian definition of freedom, and then declares victory when the Reformed position fails to meet standards it never accepted. It sounds persuasive until you actually examine what he’s claiming.

Ashby introduces a great point. I want to slow this down for a moment, because this really is the hinge. A lot of Calvinism critiques only work if you quietly redefine Calvinism as a kind of “whatever will be, will be” fatalism, where human choices are fake, meaningless, or coerced. But classic Reformed theology has never taught that.

Historically, Reformed writers have argued that God’s sovereignty and real human agency are compatible. God truly ordains. Man truly chooses. The Bible regularly speaks that way, without apologizing for it. One of the clearest examples is Acts 2:23, where Jesus is “delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God,” and at the same time, those who killed Him are morally guilty. That is not fatalism. That is providence.

Anyway, back to Tod Ashby:

Ashby: First he says that Calvinism “makes the world a sham” because God commands people to choose Him when they “can’t.” That objection only works if freedom is defined as the power of contrary choice, a will that is above nature, desire, and disposition. However, that is not a biblical definition of freedom; it’s a philosophical import.

Ashby is correct, and here’s where the confusion creeps in. Many people assume “freedom” means: “At the moment of decision, I must have equal power to choose either option, with no prior inclinations governing me.” That’s often called libertarian freedom.

The problem is that Scripture does not treat that as the baseline definition of freedom. Scripture treats human choice as real, voluntary, active, and accountable, while also describing it as morally bound. Jesus can say “whoever commits sin is a slave to sin” (John 8:34), and still hold people responsible for their choices. Paul can describe fallen man as unable to submit to God’s law (Romans 8:7-8), and still command repentance everywhere (Acts 17:30).

So the question becomes: what kind of inability are we talking about? The Bible’s emphasis is on moral inability, not mechanical inability. A sinner cannot come to Christ because he will not. His nature is hostile. It is influenced by the flesh. His loves are crooked. His desires are disordered. Nothing is forcing him against what he wants. He is choosing exactly what he wants, and that is precisely why he is accountable.

Ashby: Scripture defines freedom as acting according to one’s nature and desires, not in spite of them. Jesus doesn’t say, “You will not come to Me because you lack libertarian capacity.” He says, “You will not come to Me because you do not want to” (John 5:40). The inability is moral, not mechanical. The will is not coerced; it is enslaved. A will enslaved to sin still wills freely, eagerly, and consistently.

Yes! This is one of the most important distinctions in the entire debate. If someone tells you, “Calvinism says people are robots,” they are usually assuming that unless you have libertarian freedom, you have no meaningful freedom at all.

But in everyday life, we all recognize that we choose according to what we want. We do not experience our choices as coercion. We experience them as expression. We choose what we love, prefer, trust, and value. That is why Scripture aims at the heart. God does not merely command external behaviors. He commands love, faith, humility, and repentance. That is also why regeneration is described as God giving a new heart (Ezekiel 36:26) and why faith itself is treated as a gift (Philippians 1:29).

Ashby: So when God commands repentance, He is not play-acting. He is addressing real moral agents who act voluntarily, even while bound by their nature. Divine commands do not require libertarian ability; they require moral responsibility. Scripture never apologizes for this. Neither should we.

I agree with that. If God can only command what man has independent power to perform, then the Law collapses, the Gospel collapses, and grace becomes unnecessary. Scripture uses God’s commands to expose what we are, then to drive us to mercy. “Through the law comes knowledge of sin” (Romans 3:20). The command is real. The responsibility is real. The need for grace is real.

Ashby: Then comes his second claim, that Calvinism makes God the author of evil. This is where the argument collapses under its own weight. To say God ordains whatsoever comes to pass is not to say God commits evil, approves evil, or injects evil into creatures as a substance.

Now we are in the deep end, but we can still keep it clear.

The Bible is unashamed to say God “works all things according to the counsel of His will” (Ephesians 1:11). It also insists God is light, and in Him is no darkness at all (1 John 1:5). It also insists God is not tempted by evil and tempts no one (James 1:13). So any Christian view worth holding has to affirm both truths: God is absolutely sovereign, and God is not morally blameworthy for sin.

That means the real dispute is not “Does God govern?” The dispute is “What kind of causation are we talking about when God governs a world that includes real creatures?”

Ashby: Evil is not a “thing” God creates; it is a privation, a disorder of the will. God’s decree establishes the certainty of events; the creature’s will supplies the moral quality of those events. Same act. Different causal orders. Different intentions. This distinction is basic Christian metaphysics, affirmed long before the Reformation.

Correct. This “same act, different intentions” point is extremely biblical. Joseph’s brothers sell him into slavery. That action is sinful, hateful, and culpable. Yet Joseph can look them in the eye and say, “You meant evil against me, but God meant it for good” (Genesis 50:20). Same event. Two intentions. Two moral evaluations. The brothers bear blame. God bears none.

The cross is the clearest example. Acts 4:27-28 says Herod, Pilate, Gentiles, and Jews did what God’s hand and plan had predestined to take place. And yet they are still guilty. God ordained the event for holy purposes. They pursued the event for wicked purposes. Same historical act, different moral ownership.

Ashby: Turek then appeals to a debate story involving Norman Geisler and John Gerstner, with the rhetorical mic-drop question: “Who gave Adam the desire to sin?” followed by the verdict “contradiction.” That only sounds decisive if you assume desires must be externally injected like software updates.

This is exactly the pressure point: “If God is sovereign, then God must have inserted the sinful desire.” That is the assumption. But it is not required, and it is not how Christian theology has historically spoken about the relationship between Creator and creature.

Created beings are finite, contingent, and mutable. God is infinite, independent, and immutable. We do not live on the same plane. God is not merely a bigger creature. He is the Creator. That Creator-creature distinction matters.

Ashby: Adam did not sin because God implanted evil in him. Adam sinned because, though created upright, he was mutable. The desire arose from Adam’s own finite, contingent will when confronted with temptation. God ordained the Fall; Adam authored the sin. Those two statements are not contradictory unless you collapse all causation into one flat category, which is precisely the philosophical error being made.

Very well said. But if you are still having trouble following along, let me say this in very plain language.

God can ordain that an event will happen without becoming the sinner inside the event. God can govern the whole story without becoming morally dirty. The Bible treats God’s providence as higher-order governance, not as God doing the wickedness Himself.

When Adam sinned, Adam wanted to sin. He was not compelled against his will. His will was active. His desire was real. He turned from God. That is why the blame is his. Meanwhile, God’s decree was not a sinful desire. God’s decree was His righteous decision to permit and govern the event for His own holy purposes, including the glory of Christ in redemption (Ephesians 1:6-7).

Ashby: Calling this a “mystery” does not mean “logical contradiction.” It means we are dealing with layered causality. God as the first cause, man as the secondary cause; God ordaining the event, man intending the evil within the event. Scripture explicitly affirms both without embarrassment (Genesis 50:20; Acts 2:23; Acts 4:27–28). If that framework makes God the author of evil, then the Bible itself is guilty.

This is one of the best ways to frame it. When Christians say “mystery,” they are not saying “nonsense.” They are essentially saying “truth that exceeds full creaturely comprehension.” Christianity is full of that, and it has to be, because God is infinite and we are not.

The Trinity is not a contradiction. The incarnation is not a contradiction. Providence is not a contradiction. They are mysteries in the sense that we can speak truly, biblically, and coherently, while still running into the limits of our creaturely mind.

Ashby: Finally, the irony is that the very objection meant to rescue human freedom ends up destroying it. If desires must be self-originating in a libertarian sense, then they are either uncaused (which makes them random) or self-caused (which is incoherent). A will that determines itself without prior inclination is not free; it is unintelligible. Calvinism, by contrast, affirms what we actually experience every day; we choose what we want, and we want according to what we are. Grace doesn’t violate that structure; it redeems it.

This is a crucial philosophical point that often gets skipped. If a choice is not shaped by any inclination, any nature, any desire, any reason, any disposition, then what is it shaped by? If the answer is “nothing,” then it is randomness. If the answer is “itself,” then you have the problem of self-causation, where the will creates its own desires without already having a desire. That turns into circularity fast.

Reformed theology claims something simpler: we choose according to what we love. The tragedy of sin is that our loves are corrupted. The miracle of grace is that God changes what we love. He does not drag people kicking and screaming into the kingdom. He makes them willing (Psalm 110:3). He opens the heart (Acts 16:14). He grants repentance (2 Timothy 2:25). He gives faith (Philippians 1:29). That is why conversion is both a command and a gift.

Ashby: So no, Calvinism does not make the world a sham. It makes it intelligible. It preserves real agency, real responsibility, and a sovereign God who is holy, righteous, and never the author of evil, while still being the Lord who “works all things according to the counsel of His will” (Ephesians 1:11). The real problem here is the insistence on a definition of freedom that neither Scripture nor reason can sustain.

I believe that is the heart of the matter. And I also believe this is one reason Christianity rings true when you look at the world honestly. Scripture tells the truth about human nature. We are responsible, and we are bound. We are accountable, and we are broken. We need commands, and we need rescue. And the Gospel gives what God commands, because Christ accomplishes what sinners cannot accomplish on their own.

Ashby’s follow-up post (full text with my commentary)

Tod Ashby created another response, which was very good; this was more focused on the debate between Geisler and Gerstner. Here is the start:

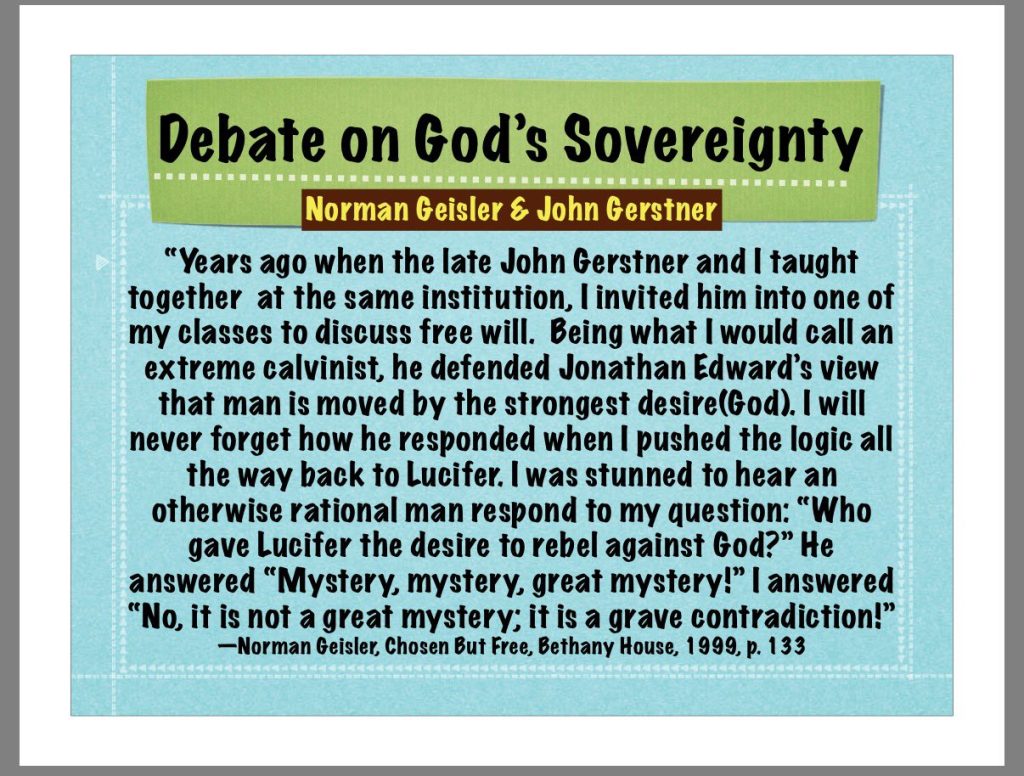

Ashby: First, Turek slightly misstated the exchange between Gerstner and Geisler. John Gerstner did not argue that “God gives man the desire of his heart” in some crude, mechanical sense, as though desires are injected wholesale. He was defending the Edwardsian point that the will always follows the strongest inclination, and that God, as first cause, orders reality without being the moral agent of creaturely sin. That distinction matters, because it’s exactly where Geisler’s charge fails.

Ashby provides a helpful clarification. A lot of people picture God “installing” desires into a person. But that is not what Puritan theologian Jonathan Edwards (or Gerstner) was trying to say.

The point is that choices are not random. The will is not floating above nature, love, and inclination. People choose for reasons, even if the reasons are sinful, even if those reasons live deep in the heart. That is why Jesus locates sin in desires (Matthew 5:28) and why James locates sin’s birth in “desire” (James 1:14–15).

Ashby: When Norman Geisler asks, “Who gave Lucifer the desire to rebel?” he is forcing a false dilemma. Either God directly authored the sinful desire, or the system collapses. But that dilemma only exists if you flatten all causation into a single category and deny the Creator/creature distinction.

Right. The dilemma assumes there are only two options:

- God directly authored the sinful desire in the same way a creature authors sin, or

- God is not sovereign over the event at all.

But that is not the menu Scripture gives us. Scripture consistently presents God as sovereign over all things while maintaining the creature’s moral responsibility within those things.

Ashby: Classical Christian theology has never done that.

This is a point that’s worth underlining. This layered view of causation did not begin in the Reformation. The Bible itself speaks this way, and the Christian tradition has worked hard to preserve both sides of the biblical testimony: God’s exhaustive providence and God’s spotless holiness.

Ashby: Lucifer was created good, upright, rational, and mutable. The desire to rebel did not need to be positively created by God as an evil object. It arose from a finite will turning away from the highest good. God decreed the event; Lucifer authored the sin. Same event. Different causal orders. Different moral ownership. That is not a contradiction unless you’ve already assumed that God and creatures operate on the same moral plane.

This “mutable” category matters. A creature can be created good without being created immutable. Only God is unchangeable in that absolute sense (Malachi 3:6). A finite, created will can turn. When it turns away from God, the moral fault belongs to the creature, not to the Creator.

And again, the Bible’s own pattern fits this. God can decree a sinful event without being the sinner. Scripture never presents God as morally compromised by His providence. He remains holy. He remains righteous. He remains just. That is not philosophical gymnastics. That is biblical realism.

Ashby: Notice Geisler’s sleight of hand. Geisler hears “mystery” and translates it as “logical incoherence.” But mystery in classical theology does not mean “A and not-A.” It means the coherence exceeds our creaturely comprehension without violating logic. The Trinity is a mystery. The incarnation is a mystery. Providence itself is a mystery. If “mystery = contradiction,” orthodox Christianity collapses immediately.

Ashby is exactly right. Christians are not allowed to throw around “contradiction” casually, because we worship the God of truth. A contradiction is “A and not-A in the same sense at the same time.” That is not what is being asserted when we say God ordains and man is responsible.

We are saying something more precise: God’s decree and man’s will operate on different levels of causation and different categories of moral ownership. That is why Scripture can affirm both without embarrassment.

And, as Ashby offers, the full breadth of theological concepts, like the Trinity, the Incarnation of Christ/Hypostatic Union, or God’s Providence, are still a mystery because we as finite humans cannot possibly grasp all of it. We only know what God has revealed about Himself. That is not a “contradiction.”

Ashby: What’s really happening is this, Geisler’s system cannot tolerate asymmetrical causation. If God determines outcomes, He must also bear moral blame, unless you allow for layered causality. But once you allow that, the Calvinist position is no longer incoherent; it’s simply biblical.

This is where I think the whole debate often lands. If someone refuses layered causation, then yes, they will feel forced to pin moral blame on God whenever God decrees an event that includes sin. But Scripture itself will not let us do that.

God’s providence is not God committing sin. God’s decree is not God committing evil. God’s governance is not God becoming morally tainted. And Scripture gives repeated examples where God’s sovereign plan includes human wickedness without God being wicked.

Ashby: Ironically, Geisler’s own libertarian framework fares worse. If Lucifer’s desire to rebel was not determined by God or by prior nature or inclination, then it was either uncaused (pure randomness) or self-caused (which is incoherent). Either way, you’ve lost moral responsibility, the very thing libertarian freedom is supposed to protect.

This point lands hard if you follow it carefully. Libertarian freedom is often presented as the great defender of responsibility. But if choices have no governing inclinations, then they become arbitrary. If they are arbitrary, they stop being morally intelligible. You can still slap the label “free” on them, but you have not explained anything. You have only renamed the problem.

Ashby: So no, calling it a “grave contradiction” doesn’t make it one. It just signals where the philosophical pressure point is.

Precisely. Strong language does not equal a strong argument. The real work is defining terms and categories carefully: freedom, ability, moral responsibility, causation, decree, intention, and the Creator-creature distinction.

Ashby: The real contradiction only appears if you refuse to let God be God and insist that creaturely freedom must operate independently of His decree. Scripture never grants that assumption. Neither should we.

Amen. Scripture’s God is not a bystander. He is not watching history unfold, wringing His hands or shrugging His shoulders and hoping things work out. He is the Supreme, Almighty Lord of heaven and earth, and He governs without sinning, rules without being blameworthy, and ordains without being the author of evil.

A quick note about the Geisler and Gerstner image

Ashby also shared an image with more quoted dialogue between Geisler and Gerstner. If you did not see it in the embedded X post/tweet above, I’ve posted it here for you to view clearly.

Closing thoughts

I’m not writing any of this to pick fights or to dunk on men who have served the church. I’m writing because I believe that God’s sovereignty is not a side topic. It is woven into the Bible’s view of salvation, providence, suffering, prayer, evangelism, and worship. A God who is truly sovereign is a God who can actually keep His promises.

And when you look at the cross, you see the clearest proof that the categories have to be layered. The most wicked act in history was also the most glorious act in history. Men meant evil. God meant good. Christ was not a victim of chaos. He was the Lamb “foreknown before the foundation of the world” (1 Peter 1:20), accomplishing redemption in real history, by a plan no human rebellion could derail.

That is not a sham world. That is a world governed by a holy King, saving sinners by a holy Savior, for the praise of His glorious grace.

Oh, and if you haven’t already, be sure to give Tod Ashby a follow if you’re on X/Twitter.

And even though I disagree with Dr. Frank Turek on this particular issue, he still produces fantastic content, and he is well worth a follow.

Read More on My Posts on Calvinism

Calvinism Explained: What Many Critics Get Wrong

Responding to the Most Common Myths About Calvinism

0 Comments